The desire to understand what is real and what is not has been central to human thought for millennia and has driven some of our greatest philosophers to tackle the question: “I think, therefore I am.” There are two Basque phrases that epitomize the dueling views of being. On one hand, ‘izena duen guztiak izatea ere badauke — everything with a name exists.’ But, at the same time, ‘izenak ez du egiten izana — a name does not make something true.’ While today, we take it as a given that we are all individuals with certain unalienable rights, that hasn’t always been the way people, including Basques, viewed things. What is more “real,” the individual or the group? These questions are at the heart of our concepts of rights and of government.

- While we don’t have any real written evidence of how ancient Basques, or proto-Basques, viewed themselves as beings, we can get some sense from analyzing myths. One thing that jumps out immediately is that characters in Basque myths are rarely given proper names. They are always referred to as, for example, “the Lady of Anboto,” “the Jentilak of Arrola,” “the Basajaunes of Muskia,” or “the Lamiñas of Bazterretxe.” That is, they are not given their own name, but the name of a place — the place lends its name to the characters.

- Of course, in the Basque Country, this practice of taking names from places extended well into the 18th century as people were known not by their parents’ names, but by the names of their houses, of their baserri. Today, those names have moved beyond the place and adopted as ancestral names, passed from parent to child, but their origins are clearly taken from places, not people. A name like Uberuaga referred not to one’s father but rather to the house one lived in.

- This suggests that the role of the individual in society was viewed very differently. Today, we are accustomed to placing the individual at the center of the system, and everything grows from there. However, in a society where places are at the heart of identity, the collective becomes the central element. Instead of individual achievement, the benefit to the group becomes the defining characteristic. People themselves become anonymous while the way their actions benefit others becomes the central story.

- From this perspective, certain themes arise around the ancient concepts of being and self. People live and die, but the group, the collective, persists, as does the place it inhabits. People are transient, but places are permanent (at least relatively). That is why places are given names and people are named after places — those places will long outlast the people. Groups — home, neighborhood, town — are eternal and constant, even if people are not.

- As described by Juan Inazio Hartsuaga Uranga, the head of some house, say Bazterretxea, is simply called Bazterretxe. If, while he is still alive, his son becomes the head of the house, the son is called Bazterretxe while the old man becomes Bazterretxe Zaharra (the Old Bazterretxe). And when he dies, he becomes Bazterretxe zena (the one who was Bazterretxe) according to the traditional use of Basque, because he cannot keep the name with him, it was never his, he was just borrowing it from the place.

- The idea that the collective is the center of identity, not the individual, means that glory and curses belong to all, not just to the perpetrator of deeds. When the people of Agerre baserri tried to steal a gold bedspread from the Jentilak, their entire house was cursed, a curse that its current inhabitants still suffer many generations later — Agerre Agerre den bitartean (as long as Agerre is Agerre) — the curse does not expire as long as the Agerre house exists.

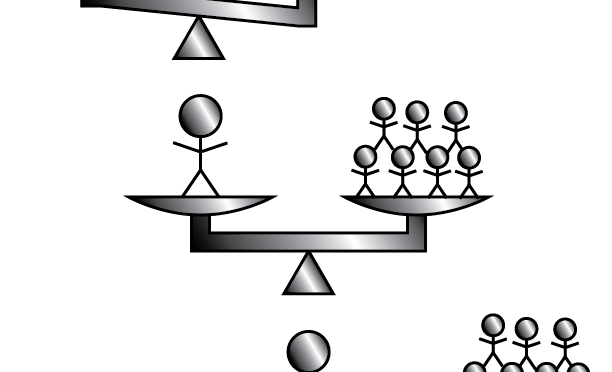

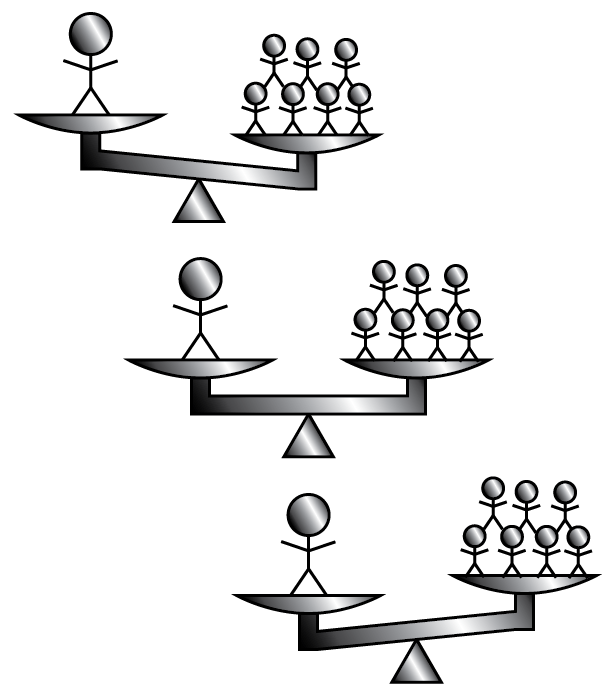

- Whether the individual or collective is at the center of society has profound consequences. In an ontology — a concept of being — that is focused on the group, such as what ancient Basque culture may have been like, society can more easily mobilize people for the greater good. However, those people also have less freedom to pursue their own interests. On the other hand, if the individual is at the center, freedom is valued more highly, but solidarity with the group and the ability to mobilize for a common goal may be weakened.

Primary source: Hartsuaga Uranga, Juan Inazio. Ontología en la Mitología Vasca. Enciclopedia Auñamendi, 2020. Available at: http://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/es/ontologia-en-la-mitologia-vasca/ar-153826/

Discover more from Buber's Basque Page

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.